Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

6 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff pivots slightly from financial instability to discuss Alexander Hamilton’s first foray into managing America’s national debt. Even readers with little interest in banking may be surprised at the level of political corruption endemic within U.S. government in 1791.

|

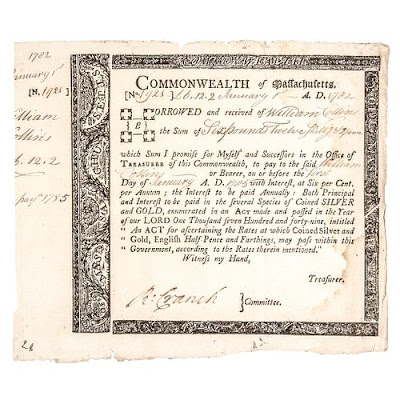

| A depreciated Massachusetts Revolutionary War bond like those Alexander Hamilton's insiders bought for mere shillings on the pound |

http://www.cautiouseconomics.com/2022/03/free-regulated-banking-14.html

III. THE FEDERAL DEBT CONTROVERSY

In 1791 Alexander Hamilton directed his new central bank, the Bank of the United States (BUS), to invest heavily in U.S. Treasury debt, uncoincidentally since he was also the Secretary of the Treasury. The story surrounding Hamilton and the debt question is a fascinating one that we will examine here.

The Revolutionary War was funded partially from debts issued by the colonial state governments. At war’s end, it was clear that many states were struggling to fully repay their ballooning war debts and their bond prices fell dramatically.

Hamilton famously convinced President George Washington to use the powers of the U.S. Treasury to assume the states’ debts and consolidate them into a single federal debt, again over the objections of Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton believed that taking on a large national debt would establish the new government’s credit in world markets and welcomed the resulting transfer of power from the states to the central government.

Furthermore he is known for calling the public debt “a national blessing.”

In a 1781 letter to his financial colleague and mentor Robert Morris, the wealthiest man in America at the time, Hamilton had already laid his plans to establish a national debt for the new United States:

“A national debt if it is not excessive will be to us a national blessing; it will be powerful cement of our union. It will also create a necessity for keeping up taxation to a degree which without being oppressive, will be a spur to industry.”

-April 30, 1781

More controversially, Hamilton convinced Washington to not only assume all state war debts, but to buy the bonds at par—full face value—even though many of the bonds traded at only 20 cents or even pennies on the dollar.

But where would the federal government find the money to buy up all these state bonds?

It would issue new federal bonds (ie. a national debt) and Hamilton would ensure there was always a willing market to buy them using a two-pronged strategy.

1) Although the BUS was legally prohibited from buying government debt directly, Hamilton’s IPO terms required subscribers to buy their shares using only 25% in gold/silver specie payments and the other 75% with federal government bonds in three one-year installments, thus creating an instant demand for U.S. Treasuries.

This share subscription rolled an enormous hoard of government bonds into the bank's coffers with interest payments profiting the BUS and its shareholders handsomely.

2) Once Hamilton’s central bank opened for business it would lend generously to his finance contacts in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston who in turn agreed to use the proceeds to buy more U.S. government bonds, pushing up securities prices and growing the large public debt Hamilton had coveted. The hapless U.S. taxpayer would then repay the government’s debt plus interest.

It was precisely the arrangement Jefferson had warned about: the BUS acting as an instrument to enrich the moneyed classes at the expense of the general public.

IV. HAMILTON INSIDERS PROSPER

Once Washington agreed to the assumption of state debts, Hamilton’s mentor Robert Morris and other political and finance associates got wind of the arrangement and immediately sent their agents up and down the Atlantic seaboard to buy up as many of the depressed state bonds as they could find.

Since word travelled very slowly using 1790’s technology Morris and Hamilton’s other colleagues were effectively armed with insider knowledge. Fully aware that the federal government was going to pay one hundred cents on the dollar, they bought up near-worthless state war bonds from anyone they could find including widows and war veterans, many of whom were permanently wounded or maimed, missing eyes, arms or legs.

As Claude Bowers’ 1925 book “Jefferson and Hamilton” describes:

“Expresses with very large sums of money on their way to North Carolina for purposes of speculation in certificates splashed and bumped over the wretched winter roads… Two fast sailing vessels, chartered by a member of Congress who had been an officer in the war, were ploughing the waters southward on a similar mission.”

“[War bonds] were coaxed from them [veterans] for five and even as low as two, shillings on the pound by speculators, including the leading members of Congress, who knew that provision for the redemption of the paper [at full value] had been made.”

“Everywhere men with capital… were feverishly pushing their advantage by preying on the ignorance of the poor.”

To pay off the federal bonds that financed the entire scheme Hamilton’s first target was a tax on whiskey and distilled spirits which instigated the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794.

Most students of U.S. history are aware that Hamilton advised military force and arrests against angry corn and grain farmers and personally accompanied the militia army to western Pennsylvania.

Not only did the farmers feel singled out, but Pennsylvania was one of the few states that had successfully paid off its war debts and its citizens and government believed it was unfair that they were now being taxed to subsidize heavily indebted states like Massachusetts and South Carolina.

Hamilton also famously argued for the execution of rebelling farmers for treason but could only secure two hangings which Washington eventually canceled by presidential pardon.

Once Hamilton’s Treasury Department purchased the depreciated state bonds at par, Morris and Hamilton’s other friends made a fortune.

John Quincy Adams wrote to his father Vice President John Adams that “Christopher Gore, the richest lawyer in Massachusetts, and one of the strongest Bay State members of Hamilton’s machine, had made an independent fortune in speculation in public funds.” (Bowers)

And according to DiLorenzo (2009):

“New York newspapers speculated that Robert Morris stood to make $18 million (more than $300 million in 2009 dollars), while Governor George Clinton of New York would pocket $5 million. Hamilton himself purchased some of the old bonds through his buying agents in Philadelphia and New York but insisted they were ‘for his brother-in-law.’”

The Economics Correspondent is a bit skeptical of the $18 million that New York newspapers speculated Robert Morris gained. Analyzing the total federal debt and federal revenues at the time, $18 million is barely mathematically possible, but as America’s richest man Robert Morris undoubtedly profited to the tune of many millions of dollars. And there is no question that many of Hamilton’s associates also made fortunes from the insider trading scheme.

Yet today Hamilton's assumption of the states' debts is lauded by liberal pundits as an unequivocal success, especially whenever the suggestion of the federal government bailing out bankrupt states and municipalities is floated (such as Detroit in 2013 and several financially distressed state governments in the post-2008 recession). No mention, of course, of the political corruption and profiteering that encompassed the bailout or the financial crisis it directly fostered.

More about that financial crisis in the next chapter.

It's no wonder the Broadway play “Hamilton” is such a success in large cities like New York and Los Angeles while Alexander Hamilton has recently become the favorite Founding Father among urban elites.

But what about banking panics? After all crisis and instability is the theme of the Economics Correspondent’s series is it not? Aside from facilitating debt, inflation, cronyism, and corruption didn’t the BUS also incite financial crises?

Absolutely. Stay tuned for the next column where we’ll return to the subject of financial instability and review how Hamilton’s dealings at the BUS precipitated America’s first financial crisis: the Panic of 1792.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.