Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

7 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs (and other Egghead Stuff) concludes his analysis of the dysfunctional U.S. National Banking System of 1863-1914, discussing more backwards regulations that bred multiple financial crises—ultimately leading to the Congressional horse trading that replaced the NBS with the Federal Reserve System.

As we discussed in the last chapter, America’s National Banking System (NBS: 1863-1914) regulations prohibited federally chartered banks from issuing paper currency unless backed 111% by U.S. government bonds.

As the Civil War national debt was paid down, banks found it impossible to acquire the bonds needed to issue cash and farmers demanded gold coin withdrawal instead to pay harvest season workers, precipitating several credit crunches and general monetary panics.

Combined with state-level unit banking laws that had already weakened American banks going back to the nation’s founding, National Banking System regulations precipitated severe banking panics in 1873, 1893, and 1907 with incipient panics in 1884, 1890, and 1896.

To go back and read Part 1 of the National Banking System, visit the Economics Correspondent’s preceding article at:

http://www.cautiouseconomics.com/2022/10/free-regulated-banking-23.html

RESERVE BANKS

But there was another destabilizing provision within the National Banking Acts that not only made financial crises worse and more frequent, but also entrenched the system politically making it harder to reform.

In the pre-NBS era of 1837-1862, state-chartered banks issued banknotes and deposits backed by their own gold and silver coin reserves and (problematically) state government bonds.

Under the NBS, federally chartered banks were no longer required to hold as large a gold or silver reserve. For reasons we’ll discuss in a moment, the National Banking Acts divided banks up into three tiers and loosened the reserve requirements for them all.

The three tiers, from smallest to largest, were:

Country banks: Thousands of tiny banks, usually unit banks with no branches, that were scattered throughout rural areas.

Reserve city banks: Larger banks in regional metro centers like Chicago, St. Louis, or Atlanta.

Central reserve city banks: A handful of large Wall Street banks.

Whereas prior to the NBS *all* banks’ reserves were comprised of gold and silver coin, the new system significantly expanded the list of what qualified as a reserve holding.

1) Country banks’ legal reserves were changed to smaller gold and silver holdings, U.S. Treasury greenbacks—which were essentially unbacked paper money—and most notably deposit accounts at reserve city banks.

2) Reserve city banks’ reserves were reduced under similar terms, the only difference being the amount of gold, silver, and greenbacks they were required to hold was even smaller than the country banks, and a larger share of their reserves were deposit accounts at central reserve city (ie. Wall Street) banks.

3) Finally central reserve city (ie. Wall Street) banks were also allowed to reduce their gold and silver holdings and back their obligations with greenbacks.

The NBS multi-tier system designed the entire industry to inflate more credit and paper money upon the same base of gold and silver reserves, replacing hard money with paper greenbacks and IOU’s from banks in larger cities.

This was the whole idea, after all, as the Union was seeking inflation and bank credit to finance the war effort.

And state banks that didn't wish to join the NBS were taxed out of existence in 1864 with a 10% federal tax on every private banknote issued.

Which brings us at last to the destabilizing element.

When the system was stressed by farmers withdrawing gold coin from their country banks, the highly inflated system collapsed on itself, exacerbating the crisis.

When farmers asked their country banks for gold coin to pay their hired hands, not only did the country banks lose reserves, contract credit and raise interest rates, they also had to tell their customers (in technical parlance)...

“Actually we don’t have enough gold physically in the vaults. We have to go get it from our reserve city bank in St. Louis.”

As thousands of regional country banks descended upon reserve banks like St. Louis for gold coin, the reserve city banks responded:

“Actually we don’t have enough gold physically in our vaults. We have to go get it from our central reserve city bank in New York.”

And as reserve city banks from across the country descended upon a handful of Wall Street central reserve city banks for gold coin, Wall Street banks responded:

“Actually we don’t have enough gold physically in our vaults. We can’t pay.”

And there was no higher tier for Wall Street banks to petition for help. They were the last level of reserve bank.

Thus in each panic what started as withdrawals from small rural banks quickly grew into systemwide bank runs which produced widespread failures and nationwide suspension of gold payments.

CALLS FOR REFORM

After the enormous Panic of 1907 America’s financial system was so shaken that Congress acknowledged the need for reform.

The National Monetary Commission was established in 1908 to study alternative systems, headed by powerful Senate Finance Committee Chairman Nelson W. Aldrich (R-RI).

Two lobbying camps quickly assembled and attempted to exert their influence on the commission.

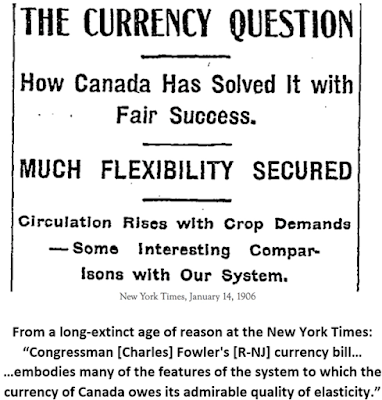

The first was a bona fide “free banking” lobby that wished to replicate the Canadian banking system.

Canada was already known for experiencing no banking panics in the near-century since its first commercial bank, the Bank of Montreal, had opened its doors while the United States had already endured twelve panics since the days of George Washington.

To both the free banking lobby and Canadian bankers themselves, the key to Canada’s soundness was no secret.

Canada had no central bank to stir up asset bubbles and crises as the First Bank of the United States and Second Bank of the United States had done during the Panics of 1792, 1797, and 1819.

Canada also had no government bondholding mandate that prevented banks from issuing currency as the National Banking System had required since 1863.

And Canada never had any unit banking laws that made branching illegal. From the very beginning Canada’s banks branched nationwide and were allowed to hold diversified loans from all corners and industries of the country.

As Charles Calomiris of Columbia University points out, Canadian bankers at the turn of the century were literally laughing at the stupidity of the American system.

But the free banking lobby was opposed by a more powerful alliance of special interests who comprised the “central banking” lobby.

State governments, small unit banks, Wall Street banks, and Senator Aldrich himself didn’t want to see the restrictions lifted since they had vested interests in seeing the NBS system preserved.

State governments and their unit banks didn’t want to see unit banking ended because they feared competition—both intrastate and interstate—would water down their monopoly profits, profits that state legislatures often reaped as shareholders in unit banks themselves.

Wall Street banks didn’t want to see the multi-tiered National Banking System ended. Even though it precipitated bank runs, crises, and suspensions, it was also good business as banks from all over the country brought more of their reserves to New York City.

And Nelson Aldrich himself was seduced by the panacea of central banking. Aldrich had toured Europe on a National Monetary Commission assignment to study other banking systems and was highly impressed; not only by what he viewed as the sophisticated operations of institutions like the Bank of England and Bank of France, but also by the elevated culture, architecture, and artistic taste of the European capitals in contrast to the provincial backwardness of the young United States.

NO REAL REFORM: A CENTRAL BANK ATOP AN ALREADY LOUSY SYSTEM

Hence Aldrich returned to America with his mind already made up. The National Monetary Commission would “search” for a solution that it had already chosen, the “inquiry” simply being a staged façade to recommend its own predetermined conclusion.

In the end, instead of allowing banks to branch unrestricted throughout their states and throughout the country, and instead of ending the system of centralization of gold reserves at large regional reserve banks, the lousy National Banking System was mostly preserved with all its flaws, only now with a central bank—the Federal Reserve System—placed atop it.

For as the Commission stated repeatedly, the American banking industry was hampered by an “inelastic currency.” Never mind the inelasticity was the direct result of federal regulations that had governed the industry for the previous half century.

The Federal Reserve Act was passed on a near party-line vote—Democrats for, Republicans against—in both houses of Congress and signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on the evening of December 23, 1913.

Aside from preserving unit banking and most National Banking System provisions there were only a few superficial changes:

-Gold reserves would be held mostly at twelve regional Federal Reserve banks.

-To solve the ”inelastic currency” problem the Federal Reserve would become monopoly issuer of paper currency, replacing private banks of issue.

-Most importantly for the special interests, if systemic liquidity stresses occurred the regional Federal Reserve banks would act as “lender of last resort” and make short term cash loans to solvent private banks on good collateral.

And as history has recorded, the establishment of the Federal Reserve hardly quelled banking panics.

The greatest financial crisis in American history, the Great Depression Panics of 1930, 1931, and 1933, occurred under the watch of the Fed just sixteen years after its founding. Only with the introduction of federal deposit insurance in 1934 did the U.S. system finally find some semblance of stability.

Incidentally, Canada didn’t have deposit insurance either as its far less regulated and far more stable system had never experienced a crisis and therefore never needed it.

However Canada finally adopted deposit insurance in 1967.