Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

8 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs gets extremely eggheady with a peek behind the curtain at the Federal Reserve’s internal financial plumbing.

|

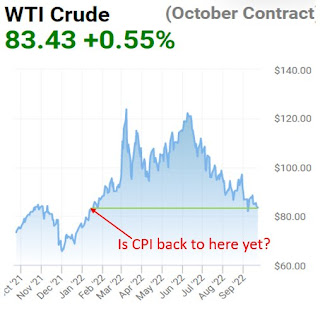

| Corridor vs Floor Operating System Visual Aid |

Americans have recently been greeted by another headline that the Federal Reserve will hike its policy rate by yet another three-quarters of a percentage point to a “range of 3.0%-3.25%.”

Most people know this means interest rates on everything at their local bank or credit union—from mortgage loans to auto loans to credit cards—will go up too.

But how exactly does the Fed raise the interest rate that private banks charge, and how does it enforce its policy “Fed Funds” rate to keep it between 3.0% and 3.25%?

Does the Fed send out “interest rate police” to America’s 5,000 banks and force them daily to lend at whatever rate the Federal Open Market Committee demands?

Obviously that would mean the creation of a coercive police state at America’s banks and would be ugly, manpower-intensive, and expensive so the Fed utilizes a different mechanism using incentives known in monetary parlance as an operating system.

RESERVES

Central banks around the world generally employ either of two monetary policy operating systems: corridor systems and floor systems.

The majority of the world’s central banks use a corridor system. The United States is an exception in that it uses a floor system, although the USA also operated a corridor system until the Bernanke Fed converted to a floor system during the 2008 financial crisis.

A corridor system can be thought of as a “scarce reserves” system whereby the central bank makes a small amount of reserves available to the financial system and encourages banks to lend out nearly as many of those reserves as is legally allowed (traditionally 90%). A floor system can be thought of as a “plentiful reserves” system where the central bank overloads banks with reserves but limits the amount of reserves they lend.

And what exactly are reserves?

Before 1914 they were gold coins, which fractionally backed the paper currency and deposit accounts of private banks.

The establishment of the Federal Reserve System in 1914 granted the central bank a monopoly on the issuance of “paper reserves”—Federal Reserve notes and commercial bank deposits at the Fed itself—although the Fed was still required to back its own paper reserves with gold by at least 40%. Therefore, the quantity of reserves the Fed could create was still limited.

Finally in 1971, when Richard Nixon severed the last remaining connection between the paper dollar and gold, reserves became “fiat.” There was no longer any limit on how many reserves the Fed could create which explains why the money supply has grown by 3,300% since 1971 while the price level has risen by 641%. Both would be impossible under a gold reserves standard.

And how do banks get reserves? They sell paper assets to the Fed—usually Treasury securities and recently also agency-backed mortgage securities—and receive an increase in their reserve balances at the central bank (hence the frequently employed term: “Federal Reserve asset purchases”).

CORRIDORS

At any given time some banks lend out all the reserves they legally can, injecting new checkbook money into the economy and expanding the money supply. However other banks may not find as many lending opportunities in their markets and hold onto idle—or what Fed officials call “excess”—reserves.

A bank that is “loaned up to the limit” may want to borrow excess reserves from another bank to lend more and increase its profits. The rate which borrowing banks pay excess reserves banks is known as the “Federal Funds rate,” the policy rate that the Fed controls.

Which leads us to the inner workings of operating systems.

As we stated before, Fed police don’t run out to every bank with guns and say “You’d better lend those excess reserves at 3.0% or else.”

Instead the Fed uses incentives. And under a corridor operating system it uses two more “administrative” rates of its own to guide the Fed Funds interbank rate to its desired target. Those are: the Fed Discount rate and the Interest on Reserves rate (IOR).

(see above chart, left)

The Discount Rate is the rate which the Fed charges banks to borrow reserves from the Fed itself.

The Interest on Reserves rate is the rate which the Fed pays private banks to hold their reserves at the Fed instead of lending them out.

The two rates create a “corridor” which limits the upside and downside of what banks will charge one another in the Fed Funds market.

How do the two administrative rates define those limits?

At a slightly simplified level, if the Fed Funds rate is 3.25%, no borrowing bank will pay more than 3.25% to another bank for reserves because it knows it can always get reserves from the Fed for 3.25%. Why pay another bank 4% for reserves when you can get them from the Fed for 3.25%?

If the Interest on Reserves rate is 3.0%, no lending bank will accept less than 3.0% interest from a borrowing bank for use of its reserves. Why risk lending your reserves to another bank for 2.5% when the Fed will pay you 3.0% to do nothing?

The Fed also changes the quantity of reserves in the system through asset purchases or sales to affect the Fed Funds rate, but the Discount and IOR rate define the “corridor” itself.

FLOORS

Under an “ample” floor system the Fed floods the industry with lots (trillions of dollars) of reserves.

In 2008 the Fed was worried that panicking bank customers might rush to withdraw their cash in a classic Great Depression style bank run.

Since the industry was on a “scarce reserves” corridor system at the time such a spike in withdrawals could cause banks to run out of reserves and fail.

Hence the Bernanke Fed went on a giant asset purchase spree and loaded the banks up with trillions of dollars in reserves to telegraph a message to the public: “Your bank has plenty of reserves now and can convert them to cash at any time. Between that and federal deposit insurance there’s no need to panic and pull your money out.”

However with trillions of dollars in reserves the banking system could easily create a major inflation if it loaned even a fraction of those new reserves out.

Hence the Fed adopted a “floor” operating system using a single administrative rate: the Interest of Excess Reserves (IOER) rate

(see above chart, right).

The IOER rate is the rate the Fed pays banks to keep their excess reserves sequestered at the Fed instead of lending them out. And a bank will not lend its excess reserves to either the public or another bank for less since it knows it can always earn IOER interest from the Fed—at zero risk and zero maturity no less, the safest interest rate there is—safer than U.S. Treasuries.

Hence the IOER rate provides a “floor” which the Fed Funds rate cannot fall below.

To keep banks from buying other paper assets with their excess reserves the Fed pays an IOER rate slightly higher than that for competing short term securities like 1-month and 3-month Treasuries (see chart).

While the Bernanke Fed did want banks to lend reserves to support economic recovery, it always sought to limit the amount of lending using IOER to avoid a major inflation.

Fed apologists argue the Fed does not “control” the Fed Funds rate and that the Fed Funds market is a “free market” between banks, but with all these Fed administrative rates it’s clear that’s not really true. The Fed has a monopoly on reserves (some free market) and then it manipulates the Fed Funds market to achieve its target rate.

RETAIL RATES AND THE USA

Whatever rate banks pay for the use of reserves—be it the Fed Funds rate or the Fed Discount rate—they will not lend to the public for a lower rate than they paid since they would lose money. Hence the Fed Funds rate itself places a floor on retail interest rates in general.

When the Fed pushes the two corridor rates up, or pushes the floor rate up, and the Fed Funds market rate rises accordingly, retail rates that the public pays go up too.

And as the public sees rates rising on mortgages, auto loans, etc… they will tend to borrow less, slowing the rate of growth of the money supply or even contracting it (ie. price inflation slows or even reverses).

The Fed was not authorized by Congress to pay interest on reserves until 2008. So although it operated a corridor system for decades prior to the financial crisis, in practice it only employed one policy rate at that time: the Fed Discount rate which kept the Fed Funds rate from rising too high.

But there was no Interest on Reserves rate to prevent the Fed Funds rate from falling too low.

So what prevented the Fed Funds rate from falling to zero under the corridor system?

Scarcity of reserves. As mentioned before, the Fed alters the quantity of reserves too and scarce excess reserves available for borrowing kept the Fed Funds rate from falling too low due to simple supply and demand (low supply = higher price).

Hence in the Economics Correspondent’s opinion, the Fed was really operating a “ceiling system” before 2008 although monetary economists who know more than him might take issue with that characterization.

Finally, the Bernanke, Yellen, and even Powell Feds have seen the floor operating system fall under heavy criticism from Congress and the public, because a floor system requires the Fed to pay risk-free interest to banks on huge levels of reserves: trillions of dollars

As of the time of this writing banks are still holding $3.2 trillion in reserves, the remnants of the giant Covid pandemic asset-purchase campaign, and the IOR rate has just been lifted to about 3.15%.

That’s about $100 billion in risk-free annual interest payments the Fed is making to private banks, all for nothing, and politically that’s pretty indefensible.

Hence the Fed has been under pressure to sell off its assets and remove reserves from the system (aka. reduce its balance sheet), and it has been doing exactly that. Reserves have fallen rapidly from $4.2 trillion in December to $3.2 trillion in July.

And throughout the 2010’s decade the Fed repeatedly said the floor operating system was a crisis-only measure and that it would revert to a corridor system soon. However it has struggled to do so, particularly when falling reserve balances combined with reserves being set aside by foreign central banks (the so-called “Foreign Repo Pool”) and the U.S. Treasury (the “Treasury General Account”) led to a mini-interest rate crisis in September of 2019.

However when the Covid pandemic struck in March of 2020 the Fed scrapped any ambitions of quickly returning to a corridor system when it ballooned reserves again, affirming its floor system for at least several more years.

The Fed’s ability/prospects for returning to a corridor system in the post-Covid, post-inflation world remains an outstanding question.

ps. The Fed’s transition from a scarce reserves corridor system to a plentiful reserves floor system in 2008 can be seen quite clearly in a long-term chart of system reserves (see St. Louis Federal Reserve link).

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTRESNS