Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

“Practically every country in the world except the United States has recognized the utility, if not the absolute necessity, of the branch system of banking in handling commodities as liquid as money or credit. A bank system without branches is on par with a city without waterworks or a country without a railroad so far as an equable distribution of credit is concerned.”

-E.L. Patterson—Canadian Bank of Commerce Superintendent—from his book “Banking Principles and Practice” (1917)

8 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff discusses more perverse consequences of legal restrictions on branch banking that plagued the United States economy for over 150 years.

In Part 1 we reviewed late 18th and early 19th century America’s political origins of legal restrictions on interstate banking and the establishment of mandated “unit banks” which could only operate from a single office.

As we left off, the Economics Correspondent discussed five negative consequences of unit banking laws, particularly those that fomented frequent financial crises and widespread failures.

To review go to:

http://www.cautiouseconomics.com/2022/01/free-regulated-11.html

In Part 2 we’ll cover six anti-competitive, anti-consumer repercussions of bank branching restrictions and measure up its performance against Canada’s unrestricted, nationally branched system.

While reading bear in mind this discussion takes place within the context of media and political accusations of U.S. banking being “laissez-faire” and “unregulated” during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

II. THE SCOURGE OF UNIT BANKING (cont.)

How do unit banking laws work against the interests of borrowers and consumers?

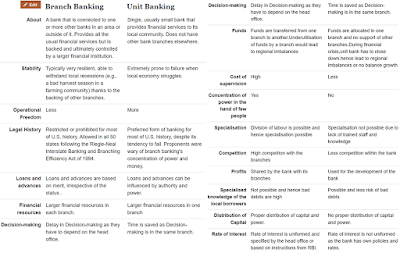

1) Lack of competition and underbanking.

It probably seems obvious that state governments drawing artificial lines around bank monopoly fiefdoms leads to less competition and it certainly did. However a specific example may illustrate just how underserved Americans were under such state restrictions.

In 1800 the four largest cities in America were New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore with populations of roughly 72,000, 41,000, 27,000 and 25,000 each.

Due to restrictive banking laws each of those cities had only two banks at the time.

Canada had no commercial banks in 1800, but at the turn of the next century remote western Canada was spotted with tiny, disparate towns. The typical incorporated township of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, or British Columbia averaged about 900 people. The same typical 900-resident township also averaged two competing bank branches (ie. two banks) operating from large headquarters in Toronto or Montreal.

Sadly for Americans, the average citizen of Medicine Hat, Alberta or Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan had as many banking choices in 1905 as Americans in New York City and Philadelphia in 1800, despite having only 2% or 3% of the population and even less commercial activity.

2) Immobility of investment capital.

Depositors in, say, Ohio may have been ardent savers, but due to interbank prohibitions their capital couldn’t fund booming railroads in Missouri. The savings of consumers in one state frequently sat unused while promising enterprises in other states starved for capital.

The Correspondent hasn’t found much material on this theory, but he suspects commercial interstate banking restrictions gave rise to the investment banking industry during the industrialized Gilded Age and made men like J.P. Morgan very wealthy. How a Gilded Age icon like Bethlehem Steel could have grown so dominant from Scranton, Pennsylvania when even intrastate capital movements were so restricted suggests the company likely sought funding from outside the commercial banking sector.

3) Geographically irregular interest rates.

Since large savings in one state were unavailable for industrial projects in other states, the United States became a patchwork of inconsistent interest rates where bank customers of one state paid several percentage points more than their neighbors across the border. Once again, in Canada where banks branched unrestricted throughout the entire country, interest rates were very comparable no matter what province the borrower lived in.

4) An inefficient, high-cost business model.

Branch banking is a very efficient system where primary functions such as accounting, loan processing, and collections can be centralized at a home office. In the 19th century branch offices were cheap to operate, needing only some specie, till cash, a teller, and perhaps a lending officer.

Under U.S. unit banking administrative functions had to be duplicated across thousands of disparate unit banks. This high cost of decentralization led to higher interest rates and less credit for consumers.

5) Depreciating private banknotes.

Under unit banking, a small local bank in Norfolk, VA would accept a gold or silver specie deposit and issue a banknote claim to its customer. As the banknote was spent, circulated through the economy, and moved further and further from Norfolk its value depreciated.

If the Bank of Norfolk's note was deposited at the Bank of St. Louis, the depositor might only get 90 cents on the dollar. The Bank of St. Louis had no idea if the Bank of Norfolk was a real institution, if it was still in business, if it had sufficient gold reserves to make good on the note, and there was a cost associated with sending the note back to Virginia and from there the gold coin back to Missouri.

Eventually innovative banknote gathering and redemption institutions such as the New England-based Suffolk Bank sprang up, going around the country and collecting disparate banknotes for over 99 cents on the dollar before delivering them to their bank of issuance for redemption.

But no Suffolk Bank was ever necessary in Canada where all banknotes were accepted virtually at par. A Bank of Toronto note issued in Ontario might find its way to deposit at the Bank of Halifax in Nova Scotia at which point it was accepted at 99 and more often 100 cents on the dollar.

Why so easy? Because the Bank of Toronto had a branch office in Halifax right across the street! And both banks had nationwide branch networks that allowed notes and reserves (both their own and their competitors') to move effortlessly throughout the country.

Large national branch networks made depositing even a Bank of Montreal note in Vancouver, BC the same as depositing it in Montreal, Quebec—much how we take effortlessly depositing a Bank of America check (headquartered in Charlotte, NC) at a Citibank branch in Los Angeles for granted in 2022.

6) Finally, there’s wildcat banking.

Wildcat banking is a favorite complaint of alleged deregulation for both New York Times columnist Paul Krugman and Joe Biden's Fed Vice Chair nominee Lael Brainard.

During a limited period of the 19th century new banks would spring up in more remote states and overissue notes, often sending their agents cross-country to eastern cities like New York and Boston to buy up assets. Wildcat bankers assumed, often correctly, that eastern banks wouldn’t go through the trouble of sending their notes long distances to the remote middle of nowhere for redemption.

Overissuance by wildcat banks has been exaggerated as a problem given that scholarly estimates place the total number of wildcat banks at “as low as several dozen and no higher than 173” (Selgin) out of some 2,450 banks chartered between 1790 and 1862.

Furthermore “wildcat banking” only plagued five states, in each case for only a couple of years, and uncoincidentally all five states were highly restricted or unit banking states.

Which leads to the one of the strongest of the many counterarguments debunking the “endemic wildcat banking problem” thesis:

Far from being the consequence of deregulation it was precisely bad interstate banking legal restrictions that made wildcat banking attractive to shady operators to begin with. Had New York and Boston banks been allowed to branch out of state, any wildcat banknote they received would quickly find its way back to its origin demanding prompt redemption through their large branch networks.

Eventually the Suffolk Bank mitigated the wildcat banking problem, but as usual Krugman gets it completely backwards by blaming lack of government oversight. Deregulated Canada never had any meaningful wildcat banking problems. During most of its free banking era Canadian banks voluntarily agreed to accept each other’s notes at par precisely because they knew other banks had wide branch networks. Any distant bank that considered engaging in wildcat practices was aware that none of its notes would stay far away for very long, thanks to the extensive branch networks of its competitors.

In Canada there were no anti-branching laws to prevent reputable banks from keeping disreputable ones in check.

III. THE DESTRUCTIVE RECORD OF UNIT BANKING

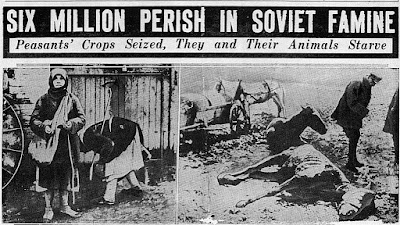

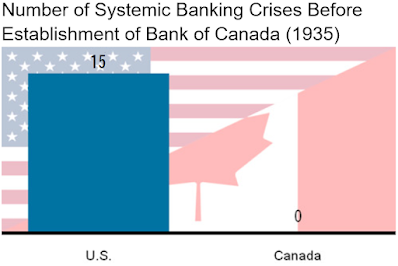

Unit banking reigned supreme in the United States from its founding, and the political alliance between local banks and state governments was a strong one for nearly two centuries. While it lasted it codified such a disparate and fragile system that the U.S. easily fell into panic during economic downturns—fifteen times from 1792 to 1933—while Canada never had a systemic crisis.

That’s worth repeating. From 1792 to 1933 the United States, bogged down by restrictive unit banking laws that kept banks tiny, weak, undercapitalized, and undiversified, experienced fifteen banking panics. Canada, with no bank branching restrictions and the industrialized world’s most deregulated system from 1845 to 1935, experienced zero systemic panics.

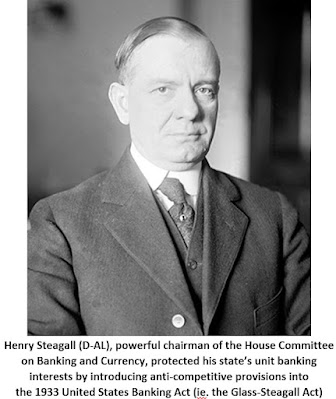

By the dawn of the Great Depression politically powerful unit banking forces even convinced Congress to pass the 1927 McFadden Act which cemented the ban on interstate bank branching at the federal level.

By 1929, 32 of America’s 48 states either restricted bank branching to a small, localized region or prohibited branch banking entirely. Only a third of states allowed unrestricted intrastate banking, and banking across state lines was prohibited by both 100% of states and the federal government.

Therefore it’s no surprise that the hardest hit states during the Great Depression’s banking panics were unit bank states. In California, a state that permitted unrestricted intrastate branching and the first state in the U.S. to reach more branches than bank companies, the incidence of failures of widely branched banks was less than one-fifth that of the entire country according to Carlson and Mitchener (2007). George Selgin of the University of Georgia has argued there were no California bank failures in the early 1930’s, but the Economics Correspondent has not yet corroborated that conclusion.

Also in the tumultuous early days of the Great Depression nearly 10,000 U.S. banks failed in the mother of all banking panics. Nearly all were unit banks and the tragedy occurred under the watch of America’s central bank, the Federal Reserve.

In Canada, where full nationwide branching was always legal, no central bank existed yet, and the country was hit every bit as hard by the depression, zero banks failed.

That’s also worth repeating:

USA: Unit bank and interstate bank restrictions + monopoly central bank of issue = nearly 10,000 bank failures.

Canada: Free, nearly laissez-fare deregulated banking industry and no central bank = zero bank failures.

In the next installment we’ll wrap up with what became of unit banking regulations after the Great Depression that they had such a large hand in creating.