Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

5 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff discusses government spending’s effect on GDP.

In Part 1 we defined GDP as total spending in the economy, or consumer spending plus business investment spending plus government purchases—purchases, not transfers—plus net exports.

In mathematical terms GDP, or Y = C + I + G + Nx.

Many people notice that government spending (G) contributes to GDP and understandably wonder if GDP reports, particularly those that reflect strong economic growth, are inflated by it.

The short answer is: "Usually not by much, but there are some notable exceptions."

There are two major factors the public might not always take into account when formulating perceptions about government spending's role in GDP.

1) The first is that only government purchases are factored into GDP, not all government spending.

Which immediately excludes any spending that is simply direct transfers.

For example, Social Security is not included in GDP because the government isn’t really buying anything (although some might say votes) but instead taking money out of workers’ paychecks and transferring it into disability and retiree pension checks.

The same is true for welfare payments, unemployment checks, federal transfers to state and local governments, direct subsidies, and most notably interest on federal debt. None of it is factored into GDP.

In the end, only purchases are factored in.

Examples of government GDP purchase activity would include military procurement of weapons, maintenance parts and services, payments to contractors for building infrastructure and public works, or medical claims payments to purchase healthcare services and medicines for Medicare or Medicaid patients.

And government payrolls, which are considered “purchased services," are also included in GDP.

But once transfers are excluded the face of government spending changes significantly. For example, it may surprise some to learn that state and local government spending is actually a larger contributor to GDP than federal spending. The federal Departments of Transportation and Education may spend a lot of money, but much of it is simply transfers to state and local governments who in turn are the real purchasers of highway construction contracts, teacher salaries and schoolbooks, and even a great deal of medical spending.

State and local governments are also large spenders on salaries of state/city law enforcement, municipal transportation workers, social workers, etc… In 2023 there were over 19 million people employed by local and state governments versus just under 5 million by the federal government (including military).

In fact, even though defense spending is only about 15% of all federal spending, military purchases and payrolls represent 56% of all GDP purchases by the federal government. Which shows you just how much of federal purchases are defense-related and, more importantly, how so much more federal government spending above and beyond defense is simply redistributing money from taxpayers to someone else’s pocket.

And state and local government purchases are 68% higher than federal purchases.

2) The second factor is government’s contribution not to GDP, but to GDP growth.

In the most recent quarter (2Q24) government purchases constituted only 17.5% of GDP (as opposed to all government spending which is closer to 37% of GDP).

But even if one day the government ballooned to the point that purchases regularly became 50% of GDP, a government of that size still wouldn’t necessarily inflate GDP growth.

The reason is in order to inflate GDP growth figures, the purchases themselves would have to grow much faster, beyond a big number like 50%.

To keep numbers simple, let’s say a $10 trillion GDP is comprised of $5 trillion in government purchases or 50%.

The following year GDP grows 3% to $10.3 trillion but let’s say government purchases remain $5 trillion which is still a huge share.

But since government purchases haven’t grown at all, none of the $300 billion or 3% in GDP growth can be attributed to government spending. In other words a huge government budget alone isn’t enough to push GDP growth up. Rather government purchases need to grow very rapidly.

This is why when a good GDP report comes out—say the recent Q2 revision to 3% annualized growth—one has to be careful about saying “Well all the growth is just government spending.” One first has to determine how much of the 3% growth was due to growth in government purchases.

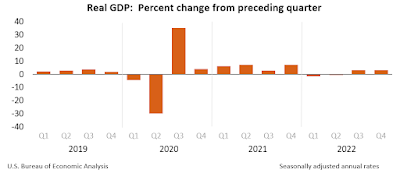

And we have it for the last quarter. According to the BEA the economy grew at an annualized rate of 3% in Q2. Contributing to that figure was a 2.9% annualized increase in the largest component—consumer spending—a 7.5% annualized increase in business investment spending, and a 2.7% annualized increase in government purchases.

So at least in the case of Q2, government purchases grew slower than the private economy—both consumer and investment spending—and therefore can’t be argued to have artificially propped up GDP growth.

However during 2023 government purchases rose at a faster rate than overall GDP in four out of four quarters. So for the entire year, yes, government purchases can be blamed for propping up GDP growth although it would take more calculations to determine by how much.

And without question there are episodes in our history when government purchases have spiked so sharply that they have completely distorted GDP growth, making it look far stronger than it really is.

These episodes would be wars and, to a lesser degree, government stimulus packages.

The most extreme example is World War II when the federal government spent nearly half of GDP on purchases, mostly for war materiel and to pay for a near tenfold increase in federal employees (mostly military).

From 1941 to 1945 real GDP technically increased by an incredible 48.7%, seemingly an economic miracle after the Great Depression of the 1930’s.

But in fact the standard of living for Americans fell during the war with shortages of basic goods and draconian rationing.

This is reflected more accurately in GDP numbers when backing government purchases out—effectively looking at only private sector GDP.

From 1941 to 1945 GDP excluding government purchases actually contracted by 12.1%, and this from a baseline of the Great Depression. To put 12.1% in perspective, at the nadir of the 2008-09 Great Recession GDP is believed to have fallen about 4%.

The contraction in WWII private sector GDP is even worse when one considers U.S. population grew by 3.7% over the same period.

In a reverse extreme example there’s the single year period of 1945-46. In the year after the war GDP fell by 11.6%, a stunning contraction that dwarfed any single year in American history except for 1932.

So 1946 must have been the year of Great Depression 2.0, right?

No, it was the diametric opposite. GDP only contracted on paper because government cut back so sharply on war spending. In fact, the private sector absolutely boomed, reflected by a 42% upsurge in private GDP (a record) including a mindboggling 140% expansion in private business investment spending (another record).

This is how much government spending during a giant war can distort GDP growth. A major slump with low living standards can look like an unprecedented economic boom while a truly unprecedented boom can look like a terrible depression.

(All calculations are based on BEA historical statistics. Links to core data available upon request.)

A similar pattern, albeit on a smaller scale, holds true in the 1950-53 period during the Korean War.

And the Obama administration’s 2009 stimulus act also inflated GDP, albeit with even smaller effects than the Korean War. And even with higher government purchases GDP was still negative/recessionary—only less negative than it would have been without all of Obama’s deficit spending.

From Q1 of 2008 to Q1 of 2010 real GDP fell by about 1.6%, the recession bottoming out in Q2 or 2009. However in that same period federal government purchases rose by 12.6%.

To which liberal Keynesian economists argue “See, if the government hadn’t spent all that extra money GDP would have fallen more, meaning a deeper recession.”

Free market economists would counter that “Government spending and blowing money on cash for clunkers and other wasteful ‘shovel-ready’ projects doesn’t mean a stronger economy just because the dollar numbers can be added to a GDP ledger.”

But that’s another debate entirely.

In upcoming columns we’ll talk about annualized GDP, comparing GDP between countries, and a small GDP consumption vs. investment controversy.