lick here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

7 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff launches an analysis of the history and destructive impact of destabilizing regulations in American banking, starting with the nation's founding.

|

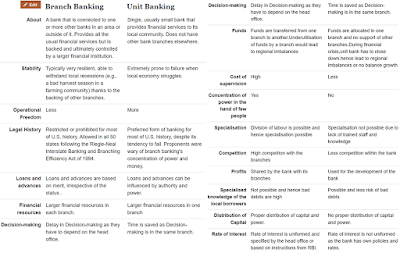

| Unit vs Branch Banking (click to enlarge) |

Since the 2008 financial crisis America’s newspapers, news networks, and most elected officials and academics have cited the debacle as a reminder to the public: Deregulating banks leads to destabilization and panic while government regulation promotes smoothly functioning finance.

Aside from the problem that in the three decades prior to 2008 American banks were subject to four new government regulations for every one removed or rewritten (Horwitz, Boettke - 2010), the real fallacy from the experts is they seem completely unaware that the entire history of North American banking demonstrates precisely the opposite.

Namely, during the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries the United States operated the industrialized world’s most regulated banking system while its northern neighbor Canada possessed the second freest (1817-1844) and then most laissez-faire banking system (1845-1935).

The results were the opposite of what the “experts” causally assume: During Canada’s 118-year “free banking" era the United States endured at least thirteen bona fide banking crises while Canada had zero.

History provides firm and easily understood reasons for this contrast, but you’ll never hear our politicians or the New York Times mention it. So read on to learn more about why America’s most regulated banking system was also the world’s most crisis prone.

I. AMERICAN BANKING: CONCEIVED IN CRONY CAPITALISM

“At the start of the [20th] century, virtually all states maintained unit banking laws, which restricted banks from opening subsidiary offices called branches.”

-Russell Settle, “The Impact of Banking and Fiscal Policies on State-level Economic Growth.” (1999)

In America’s early days banking was an infantile industry. The Constitution didn’t grant the federal government authority to charter banks, therefore that function fell to the states.

Furthermore, there was no income tax and the Constitution granted exclusive power to levy tariffs to the federal government, so from the very beginning the states were pressed to find a reliable source of revenue.

These two constitutional restrictions led the states to zero in on an obvious revenue target: banks. By the 1790’s legislatures were imposing rules and restrictions on America’s handful of banks to guarantee a flow of funds into their government coffers.

The first step was to demand financial favors from banks in exchange for permission to open as a limited liability enterprise. To secure a new charter, banks paid handsome fees to state legislatures.

Charters were also granted on a temporary basis by design. To renew a charter, banks then had to pay a hefty fee or “bonus.”

Banks also agreed to lend plentifully to state legislatures at reduced interest rates. One mechanism for realizing this arrangement was a common restriction that banks were prohibited from issuing paper currency unless fully backed by state government bonds—an arrangement the federal government would duplicate during the Civil War with truly disastrous results to be covered in a future article.

State governments also secured revenue by becoming bank shareholders. As legislatures were typically short of money they passed laws requiring banks to lend them the investment funds which were plowed right back into shares of bank stock. The loan was then slowly repaid over time out of dividend payouts.

By the 1830's the states were collectively receiving one-third of their revenue from these crony bank/government arrangements (Sylla, Ledger, Wallis - 1987).

These business-government partnerships may already sound like fertile ground for corruption and they were, but how did all these regulations lead to banking instability?

With the states’ financial interests now aligned with those of the banks, legislatures had strong incentives to keep in-state banking highly profitable and free from competition.

Thus began the rise of interstate banking restrictions and unit banking laws.

Every state in the USA, from its early days to well into the mid-20th century, adopted interstate banking restrictions that prohibited any bank incorporated in one state from opening a branch office in another state.

The fiscal logic was sound: Why allow an out-of-state bank onto your turf? Their profits will be redirected to another state treasury. And the added competition will lower your own banks’ profits and therefore your state government’s as well.

Many states went further and restricted branching even within their own borders.

Two venerable banks, both of which claim to be the nation’s oldest still in operation—the Bank of New York (today Bank of New York Mellon Corporation) and the Bank of Massachusetts (today part of Bank of America)—opened in 1784 and were granted state-sanctioned monopolies within New York and Boston respectively.

A broader example is Pennsylvania’s 1814 Omnibus Banking Act which divided the state into 27 regions and allowed 41 bank charters, each region being limited to just one or two banks.

From the politician’s standpoint, why allow too much banking competition even inside your own state? It will only water down profits and deplete payments to your treasury.

But many states went even further than Pennsylvania and became “unit bank” states, meaning by law a bank could only have one office and no branches whatsoever. Statutory language often specifically mandated “no more than one building” allowed for a bank’s operations. Thus entire states were dotted with dozens and eventually hundreds of local bank monopolies.

Unit bankers liked this rent-seeking arrangement too. Why not pay the politicians off if they grant you a local monopoly? You never have to worry about another bank moving into your market and stealing your customers.

Far from the laissez-faire mythology portrayed by today’s media and uninformed intellectuals, American banking began as an exercise in mercantilism writ large, not surprising considering it was during this same period that England was blocking its own banks from growing too large or branching.

But as the U.S. was about to learn, unit banking comes with huge liabilities and downsides.

II. THE SCOURGE OF UNIT BANKING

The name “unit banking” may sound unexciting and fall short of inspiring great interest, but it’s hard to understate the strain these laws placed upon the U.S. banking system for over 150 years.

Unit banking’s legal restrictions fomented multiple stability and commercial development problems for the nation..

In his study on the subject the Economics Correspondent has unveiled eleven in particular, although there could be more. Five promote instability and panics while six simply retard economic growth and work to the detriment of consumers.

To wrap up this column we’ll discuss the five destabilizing problems and save the remainder for the next installment.

1. No loan diversification.

This may be the most self-evident. If a bank has only one office in a local town and is forbidden from branching then its fate lies entirely with the local economy. Unit banks all across Iowa can easily fail if the price of corn plummets, banks on the Canadian border can fail if a new tariff reduces bilateral trade, or banks throughout mining towns can collapse if the demand for the local ore falls.

In Canada, where unit banking restrictions didn’t exist and banks quickly branched across the country, loan portfolios were highly diversified and risk was spread across geographic regions which in turn promoted systemic resilience.

2. No deposits diversification.

A unit bank in a small town could be heavily dependent on one or two wealthy locals for its deposit base. During a downturn one large withdrawal could ruin the bank unless it held an oversized silver/gold reserve. And taking that precaution meant less lending and an underbanked community whose economic development was stunted.

Widely branched banks in Canada collected deposits from vastly more customers from across the country.

3. Talent and regulators spread too thin

In Marcus Nadler and Jules Bogen’s “The Banking Crisis: The End of an Epoch,” unit banking is criticized as fundamentally lacking since "No country boasts enough talented banking management to supply several thousand individual institutions with able direction."

It’s a lot harder to find competent presidents and executives for 20,000 banks than a few hundred banks or a few dozen.

Moreover, to the extent one supports government regulation of banks, unit banking makes that task extremely difficult. As Nadler and Bogen point out, overseeing 20,000 unit banks "is in practice an impossible task for the regulatory authorities.” Fraud and shenanigans are much more likely to be overlooked when regulators have to track thousands of firms.

4. Immobility of reserves during financial distress

In times of turmoil unit banks experiencing deposit runs lived or died on their own reserve base, and frequently failed. But a widely branched bank, as was common in Canada, could easily move reserves from a prosperous part of the country to a distressed one.

If depositors in Manitoba worried they might not be able to withdraw specie as the falling price of wheat and nonperforming farm loans stressed local banks, a nationally branched bank could transfer reserves from its branches in a booming shipping area like Nova Scotia. After a few days customers would notice withdrawals proceeding smoothly without bank closings, regain their confidence, and redeposit their money. A crisis was averted.

No such accommodation was possible under U.S. unit banking and bank runs often led to bank failures or at minimum widespread suspension of withdrawals.

5. Lack of coordination between banks during financial distress

Canada’s smaller number of large, nationally branched banks participated in a mutual clearinghouse system and communicated regularly. If one bank experienced liquidity issues, other banks would often agree to make emergency loans or even acquire the bank. This was in all their interests to stem a wider panic, and if the troubled bank was still solvent such an emergency loan or buyout could even be profitable.

Was interbank communication as good in the United States?

Consider that in 1914, coincident with the establishment of the Federal Reserve System, the United States had over 27,000 banks of which 95% had no branches (!) and the remainder had an average of only five branches (!), the product of unit banking regulations.

Under such a fractured and divided system not only was it impossible to coordinate emergency lending among thousands of banks, buyouts and large-scale capital were also impeded from crossing state lines. It was virtually impossible for a larger, healthy commercial bank in New York City to rescue or acquire a small, distressed bank in Nebraska which in turn failed.

The best the U.S. could do was rely on investment bankers, who weren’t bound to commercial bank rules, to coordinate what rescues and buyouts they could as J.P. Morgan did famously during the great Panics of 1893 and 1907.

However even J.P. Morgan couldn’t coordinate rescues among 27,000 banks in times of distress. It was just too many institutions and sets of books to pore over in the heat of an emergency.

In the next installment we’ll review the six remaining problems created by unit banking and its macroeconomic consequences.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.