Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

3 MIN READ - Cautious Rockers may have caught on that the Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff aspires to be a student of communist regimes, particularly the Soviet Union from Lenin through Stalin (1917-1953) and China under Mao Zedong through Deng Xiaoping (1949-1992).

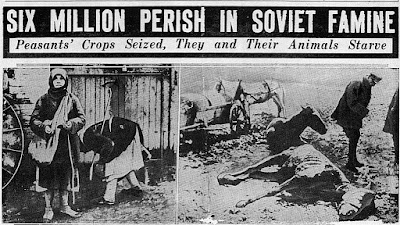

With a present-day Russia/Ukraine crisis brewing, the Correspondent is coincidentally in the middle of Anne Applebaum’s “Red Famine,” a history of the Ukrainian Holodomor “terror famine” of 1932-33, when Joseph Stalin deliberately starved approximately four million Ukrainians to death—plus three to four million more in Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, and Western Siberia—in a successful campaign to crush any resistance to occupation, Sovietization, and forced collectivization of agriculture.

Here's an excerpt from the chapter on 1919, when Vladimir Lenin first attempted to gain control over Ukraine using a divide-and-conquer form of class warfare that pitted “rich” peasant against “poor" peasant.

Although Ukrainian nationalist sentiment was strong enough to overcome the class warfare strategy, leading Stalin to starve the country into submission later instead, readers might notice the Soviets’ aborted 1919 approach is far from dead elsewhere in the modern world.

From Applebaum:

“[Bolshevik People’s Commissar of Food Collection in Ukraine Alexander] Shlikhter chose a more sophisticated form of violence. He created a new class system in the villages, first naming and identifying new categories of peasants, and then encouraging antagonism between them….”

“…The Bolsheviks, with their rigid Marxist training and hierarchical way of seeing the world, insisted on more formal markers. Eventually they would define three categories of peasant: kulaks, or wealthy peasants; seredniaks, or middle peasants; and bedniaks, or poor peasants. But at this stage they sought mainly to define who would be the victims of their revolution and who would be the beneficiaries…”

“…Very quickly, the kulaks became one of the most important Bolshevik scapegoats, the group blamed most often for the failure of Bolshevik agriculture and food distribution. While attacking the kulaks, Shlikhter simultaneously created a new class of allies through the institution of ‘poor peasants’…”

“…Under his direction, Red Army soldiers and Russian agitators moved from village to village, recruiting the least successful, least productive, most opportunistic peasants and offering them power, privileges, and land confiscated from their neighbours. In exchange, these carefully recruited collaborators were expected to find and confiscate the ‘grain surpluses’ of their neighbours. These mandatory grain collections – or prodrazvyorstka – created overwhelming anger and resentment, neither of which ever really went away.”

“These two newly created village groups defined one another as mortal enemies. The kulaks understood perfectly well that the komnezamy [‘poor peasant’ committees] had been set up to destroy them; the komnezamy equally understood perfectly well that their future status depended upon their ability to destroy the kulaks…”

“… Tasked with confiscating land from their wealthier neighbours, they unsurprisingly met with fierce resistance. In response, a handful of komnezam members formed an armed ‘revolutionary committee’, which, Nyzhnyk recalled, imposed immediate, drastic measures: ‘kulaks and religious groups were banned from holding meetings without the permission of the revolutionary committee, weapons were confiscated from kulaks, guards were placed around the village and secret surveillance of the kulaks was set up as well’”

“Not all of these measures were ordered or sanctioned from above. But by telling the poor peasants’ committees that their welfare depended on robbing the kulaks, Shlikhter knew that he was instigating a vicious class war. The komnezamy, he wrote later, were meant to ‘bring the socialist revolution into the countryside’ by ensuring the ‘destruction of the political and economic rule of the kulak’…”

“…At one of the low moments of the [Russian] civil war, in March 1918, Trotsky told a meeting of the Soviet and Trade Unions that food had to be ‘requisitioned for the Red Army at all costs’. Moreover, he seemed positively enthusiastic about the consequences: ‘If the requisition meant civil war between the kulaks and the poorer elements of the villages, then long live this civil war!’”

“A decade later Stalin would use the same rhetoric. But even in 1919 the Bolsheviks were actively seeking to deepen divisions inside the villages, to use anger and resentment to further their policy.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.