Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

6 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff closes his miniseries on legal branch banking restrictions that destabilized America’s banking system, making it crisis-prone from the nation’s founding through the Great Depression. In this last installment we’ll find out what happened to those awful unit banking laws. (Hint: even the Great Depression wasn’t lesson enough for politicians to repeal them)

For those who missed unit banking's origins and perverse effects, Parts 1 and 2 are available at:

http://www.cautiouseconomics.com/2022/01/free-regulated-11.html

http://www.cautiouseconomics.com/2022/01/free-regulated-12.html

IV. UNIT BANKING DURING/AFTER THE GREAT DEPRESSION

In the aftermath of the unmitigated disaster of the early 1930’s, virtually everyone in Congress knew that unit banking was a fatal weakness in America’s broken and uniquely overregulated financial system.

However even as the U.S. economy lay in ruins, unit banking forces were still strong enough to prevent meaningful reform. Instead of throwing out the destabilizing regulations, pro-unit bank politicians not only succeeded in preserving the broken framework, but even managed to pass additional unit bank protections at the federal level.

Within the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act’s many provisions, unit bankers got Regulation Q passed which prohibited banks from paying interest on deposits. The official rationale was that paying interest on deposits inclined banks to make higher yielding, riskier loans.

But the real impetus was limiting competition. Unit banks with monopolies in local areas were becoming more worried about competition as the automobile was replacing the horse, making it easier for customers to do regular business with other banks at greater distances. Unit banks wanted to make neighboring banks two counties away less attractive by prohibiting the competitive tactic of paying interest to pick off customers.

More consequential was the establishment of federal deposit insurance, another provision of Glass-Steagall.

Instead of protecting depositors by legalizing unrestricted branching and greater loan diversification, unit banks wished to avoid the prospect of new competition by preserving the fragile unit banking system but laying depositor risk at the feet of the FDIC instead.

Indeed, according to Charles Calomiris at Columbia University, between 1880 and 1933 there had already been 150 attempts in Congress to pass federal deposit insurance legislation, nearly always introduced by representatives from unit banking states. Every proposal had failed, but the crisis atmosphere of the Great Depression finally delivered unit banks the legislative victory they had unsuccessfully sought for fifty years.

Deposit insurance is a complicated subject. Not only is deposit insurance unnecessary in an already stable, unrestricted system such as Canada's, it also introduces moral hazard since banks can offload responsibility for their depositors onto the insurance fund. Indeed, Canada had no deposit insurance until 1967 and never experienced a banking crisis.

However, given the weaknesses created by legal restrictions on branching in the United States, combined with the destabilizing machinations of the Federal Reserve, post-1933 federal deposit insurance did go a long way towards stemming future bank runs from nervous depositors. Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz commented in their treatise that:

“Federal insurance of bank deposits was the most important structural change in the banking system to result from the 1933 panic, and, indeed in our view the structural change most conducive to monetary stability since state bank notes were taxed out of existence immediately after the Civil War.”

-A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 (1963)

Unfortunately, although it was FDIC member banks that paid into the fund, not taxpayers, it was ultimately prudent banks that ended up subsidizing reckless banks when the latter failed. And the taxpayer was forced to fund deposit guarantees in the early 1990's when the FSLIC became insolvent during the S&L Crisis.

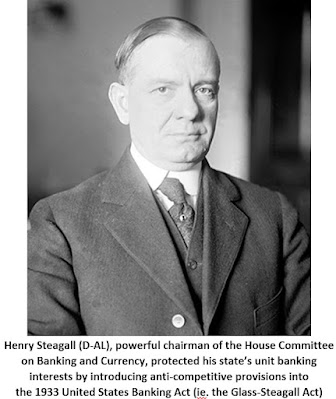

Therefore it should be no surprise to readers that the name Steagall in the Glass-Steagall Act belonged to Congressman Henry Steagall of Alabama, a unit banking state.

Steagall’s primary interest when drawing up 1930’s banking “reform” was protecting the revenue stream of his own state’s legislature and protecting Alabama unit banks from outside and intrastate competition. From his powerful chairmanship on the House Committee on Banking and Currency he was able to not only save the unstable unit banking system, but bolster it as well with new anti-competitive and bailout measures.

Even Wikipedia understands Steagall's motives in its article on the 1933 Banking Act:

"...the Glass bill passed the Senate in an overwhelming 54-9 vote on January 25, 1933... In the House of Representatives, Representative Steagall opposed even the revised Glass bill with its limited permission for branch banking. Steagall wanted to protect unit banks, and bank depositors, by establishing federal deposit insurance..."

V. LONG OVERDUE: UNIT BANKING’S EVENTUAL REPEAL

The dysfunctional unit banking system only began to fray slightly in the 1950’s as large banks attempted to use holding companies as workarounds to bypass interstate branching regulations.

But once again unit banking political forces countered, getting the Bank Holding Act of 1956 passed which decreed bank holding companies headquartered in one state were banned from acquiring a bank in another state.

It was only during the inflation of the 1970’s that the regime finally began to unravel. Unable to pay interest on deposits due to Regulation Q of Glass-Stegall, banks began to lose customers as inflation reached high single and double-digit levels. This was the age when banks compensated for lack of interest on deposits by offering laughable gifts like toasters to open a new account. Faced with the existential threat to the industry Regulation Q was finally repealed under the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980.

The political power of unit banking forces also waned in the latter 20th century as the United States became more urbanized. City dwellers weren’t as willing to put up with just one or two banks as rural residents, and the cities’ voters were by now outnumbering the countryside’s. At minimum more and more states were allowing wider intrastate competition (see progression to 1990 in attached chart).

The next nail in the coffin was ATM’s. In 1983 when Buffalo-based Marine Midland Bank installed a grocery store ATM that participated in an interstate ATM network, the Independent Bankers Association recognized the nascent threat and filed suit claiming the ATM violated intrastate and interstate branch banking laws.

The case went to the Supreme Court which ruled, by a single vote, that an ATM is not a branch office and is therefore legal. Legally deemed “not a branch,” ATM’s began popping up everywhere, dispensing cash and accepting deposits on behalf of banks all over the country.

With the S&L Crisis of the 1980’s the federal government repealed certain interstate restrictions within the 1956 Bank Holding Act and states began allowing out-of-state banks to acquire their failing institutions in interstate reciprocal merging agreements. Between 1984 and 1988 thirty-eight states entered such agreements.

The writing was on the wall for unit banking as the states themselves, having long since enacted their own income taxes, were prioritizing saving their banks and S&L’s over maintaining intrastate monopolies.

The last remaining vestiges of unit banking were finally repealed when the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 was signed into law by President Bill Clinton, making nationwide branching fully legal.

However, in a cruel irony, buried within the legislation that finally closed the chapter on two centuries of destabilizing interstate banking restrictions lied a mandate that federally chartered banks must submit to Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) compliance reviews to receive permission to expand their branch networks or venture into other lines of business.

If federal regulators deemed a bank wasn’t making enough loans in low-income areas or to low-income borrowers, it denied that bank’s request to branch, effectively reverting back to the anti-branching arrangement they were supposed to end.

So Congress traded one destabilizing bank regulation for another destabilizing bank regulation, the latter being a major contributor to the 2008 financial crisis. By 2007 over $6 trillion in loan commitments were made by banks under Community Reinvestment Act mandates with over $1 trillion of actual money loaned out.

MORE TO COME

And if you think unit banking was bad enough for America, brace yourself. It was only one of a plethora of state and federal regulatory restrictions that weakened the nation’s banking system.

Stay tuned for the next Free vs Regulated Banking chapter where we’ll discuss America’s first two central banks—the abortive First and Second Banks of the United States—which spawned several banking panics themselves.

And after that we’ll examine the federal government’s dreadful National Banking System of 1862-1913 which vaulted America into a dubious first place: the industrialized world’s undisputed champion of banking crises.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.