Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

6 MIN READ - The Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff at last wraps up his series on inflation and deflation fallacies with its most eggheady column saved for last. What about those complex counterarguments defending the government's position on the causes of inflation?

IV. MORE SOPHISTICATED COUNTERARGUMENTS: “WHAT IF CONSUMERS HAVE MORE MONEY” AND “COST-PUSH BEGETS FALLING OUTPUT”

As we discussed in Part 1, most government-provided alibis for inflation (other than moneyprinting by the central bank) can be proven fallacious due to the following axiom derived from the Equation of Exchange:

***If consumers and firms are forced to spend more money on any one sector of the economy, they will necessarily have less money left over to spend on other sectors, and the subsequent fall in demand will tend to lower prices for other goods and services.***

In this final chapter we’ll look at some counterarguments to this axiom by proponents of the “cost-push” and “full employment wage pressures” theories.

To read more about "cost push" and "demand full" theories go to Part 1 at:

http://www.cautiouseconomics.com/2020/12/inflation-currencies09.html

The objections are:

1) “The claim that ‘If consumers pay more for certain products they will have less money left over to buy other goods and services which will tend to fall in price is not necessarily true. Consumers can spend more for certain products and still have plenty of money left over if their incomes are higher.”

While this is rarely the case, the counter omits one very serious problem.

The only way all those consumers can have higher incomes is either a) the money supply has been inflated, b) monetary velocity has increased, or some combination of the two. In which case the true cause of the inflation is still not cost-push due to some more expensive commodity like oil, but rather those same old traditional causes to begin with: a larger money supply or higher velocity.

So the counterargument by its very logic places blame right back to the very culprit it's trying to exonerate.

Here’s another one:

2) “Yes, it’s true that ‘If consumers pay more for certain products they will have less money left over to buy other goods and services which will tend to fall in price.’ But as those prices fall, many firms will lose money or even go bankrupt resulting in lower output of their goods and services. So in the end the resulting fall in real GDP/output ultimately proves the cost-push inflation model.”

This one will take a little more time.

There is definitely a kernel of truth in this theory. If we use an extreme example, what if food prices were to rise fivefold instantly? A lot of consumers would be forced to set aside a huge portion of their budgets just to eat. Then car, leisure, apparel, electronics, jewelry, and other purchases would suffer horribly as would prices for all those products, ultimately leading to business failures and a lot less production in all those sectors. When production falls enough there are, in theory, the same number of dollars chasing fewer goods and voila, inflation—at least according to government economists.

The problem is where this scenario necessarily leads us. Namely, rapidly falling output is itself the definition of a recession—two consecutive quarters of it at least.

So if prices rise for 50 years straight, can the economy be in recession for 50 straight years? Of course not.

Therefore…

If inflation is climbing but real GDP is growing or at least stagnant then the “cost push leading to falling output” explanation is invalid.

That rules out the theory through at least 77%-85% of recent U.S. history.

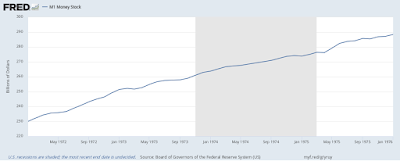

Let’s take the famous stagflation era of the 1970’s for example, when government economists were blaming cost-push, wage pressures, the weather, and every other culprit they could find other than the central bank. The economy expanded in 31 of the decade’s 40 quarters (77.5%), yet prices were rising rapidly throughout the entire decade (see link, shaded areas denote recession).

So cost-push pressures can’t explain inflation for most of that lethargic decade, yet government economists were publicly blaming it the entire time.

Furthermore, during the 1980’s and 1990’s the economy was in expansion for 68 of 80 quarters (85%) and yet inflation was present all throughout—albeit at a lower pace. Again, cost-push simply has to be ruled out for most of that twenty year period.

In the end it’s usually all about the money. Everything else is just a smokescreen.

--------------------

ps. For those interested in learning more about debunking official government rationalizations for inflation the Correspondent highly recommends Henry Hazlitt’s 1960 classic “What You Should Know About Inflation” available free at the Ludwig Von Mises Institute website.

https://mises.org/library/what-you-should-know-about-inflation-0

Hazlitt is an adherent of the Austrian School and not a Monetarist, therefore he doesn’t promote the role of velocity in inflation. Nevertheless his placement of primary blame on the central bank, the money supply, and particularly his masterful disparagement of official government “excuses” for inflation is a wonderful read.

Hazlitt is particularly skilled at writing in nontechnical terms for the noneconomist and delivering his message in short, easily digested chapters.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.