5 MIN READ - The first of a few articles on GDP from the Cautious Optimism Correspondent for Economic Affairs and Other Egghead Stuff.

|

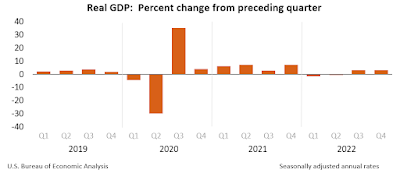

| Annualized GDP growth rates by quarter |

In late August we saw a revision of second quarter GDP to 3.0% annualized growth, and in late October we should get preliminary estimates for third quarter GDP.

But just what does this GDP number mean? And is it accurate or reliable?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the economist’s attempt to measure the output/production of all goods and services in any economy.

More importantly to those reading the news, the change in GDP—sometimes reported as “GDP grew by 2.5%”—is an attempt to measure whether economic output is growing or contracting and by how much.

But just how reliable a measure is GDP?

Well in the Economics Correspondent’s opinion GDP isn't perfect, but it's still a pretty good measure considering the immense size and complexity of an economy like the US.

Let’s start with one of the far from perfect things which, to the Correspondent’s knowledge, no one has been able to improve on: mathematically measuring “output.”

If the U.S. economy were simple and only produced one thing—say, pencils of a uniform size and quality—then measuring economic growth without GDP would be easy. If the economy produces 100 pencils in 2023 and 105 pencils in 2024, and nothing else, then we could easily argue "economic output grew by 5%."

But of course a national economy, especially the size of the U.S. economy, is hardly that simple. In fact a mindboggling number and variety of goods and services are produced in the U.S. every year, and of varying quality. The buyer’s subjective assessment of the relative value of those products, whether the buyer is a consumer, a business, or the government, is impossible to nail down. Even something as ridiculously simple as a single consumer may value the same item—say, a Big Mac—more on Saturday night than when he doesn't feel like McDonalds on Tuesday afternoon.

So enlarging our economy from one to two products (unlike 105 pencils being 5% greater than 100 pencils), how much larger is the economy overall if it produces 5% more bottles of wine and 10% more symphony concert show tickets? The Correspondent might value a bottle of wine over a ticket to the symphony, but I can guarantee you his mother would value the concert ticket over the wine.

With the subjective values of just two types of products—never mind the brand, year, and grape varietal of wines and the various calendar shows for multiple symphony orchestras—being so difficult to assess you can imagine how hard it would be to calculate for the countless products and services made by the U.S. economy every year.

Hence by far the best method economists have of measuring the value of those countless products and services, and their subjective value to consumers, is dollar spending.

Which brings us to how GDP is measured. The buyer’s valuation of bananas versus oranges versus hiking boots versus bicycle tires is best defined by how much money they’re willing to and actually spend on those things.

While this is not a perfect method, the Economics Correspondent so far hasn’t heard of a measurement process that’s better.

SIMPLE GDP MATH

Which brings us to the spending components in GDP’s fairly simple calculation. For a very long time GDP has been defined as the sum of four types of spending.

1. Consumer spending, or C

2. Business investment spending, or I

3. Government purchases, or G

4. Net exports, meaning dollar value of exports minus imports, or Nx

In mathematical terms, the economist’s formula for GDP is:

Y = C + I + G + Nx

Some critics might challenge this formula and argue “Well just because a shirtmaker charges $200 for his shirts doesn’t make them worth that much. Therefore economic output is being inflated."

To which the Correspondent counters “Well if a consumer pays $200 then it must be worth $200 to him. Otherwise he wouldn't have bought it.”

And “If not enough consumers are willing to buy all the shirts at $200 each, we know businesses tend to lower prices until demand is adequately stimulated to clear the market. If consumers buy up all the remaining shirts at $100, the lower price of those shirts will be reflected in (C)onsumer spending. If no one is willing to buy any of the shirts, then they don’t sell and are not included in GDP that year.”

That’s a pretty fair system.

Incidentally, if you want to see the components of C, I, G, and Nx measured in practice, the Bureau of Economic Analysis or BEA keeps a database of GDP going back to 1929 with measurements of the various components and even breaks down spending activity within each one. For example, Business (I)nvestment spending might be broken down into "structures" and "equipment" while (C)onsumption spending might be broken down into "durable" and "nondurable" goods.

There’s a link to the BEA GDP database at the end of the article.

WHAT ABOUT INFLATION’S EFFECT ON SPENDING?

One more thing about GDP that comes up a lot in discussion: Is it artificially boosted by inflation?

The simple answer is no... usually.

The headline reported number we read in the news every quarter is technically "real GDP,” or total dollar spending adjusted downward by the official inflation rate.

What’s less commonly reported is the actual dollar figure, inflated by rising prices and all, known as “nominal GDP.” So when you read a news story that says “The U.S. has a $28 trillion economy,” they’re using the nominal number.

If you read a story a year ago that “The U.S. has a $26.4 trillion economy” and you get out your calculator, you might think that meant GDP grew by 6% in one year ($26.4T x 1.06 = $28T).

Well nominal GDP did grow by 6%, but that’s because prices rose 3.5% due to inflation. The growth in actual output (real GDP) was only 2.5% which is the real “GDP report” growth number that makes bigger headlines.

This is also why if you hear “The U.S. had a $7.15 trillion economy in early 1994” you definitely shouldn’t think to yourself “Wow, the U.S. economy is on a tear. Output has quadruped in the last thirty years!”

A gain of $7.15 trillion to $28.6 trillion is comparing nominal GDP numbers, which means it’s been inflated by, well…. inflation again.

To measure how much the output of goods and services has grown in real terms since early 1994 you should compare real GDP from one period to real GDP from the other. Granted, the measure in prices will have to use the same price index standard for both periods (for example, “both measured in 2017 dollars”) but the percentage gain will be a lot more accurate.

And just how much has U.S. real GDP grown since early 1994? Has it quadrupled?

No, adjusting for inflation real output has really grown by 109% in thirty years. Not bad, but slightly more than double in real terms versus quadruple in nominal terms. That's how much impact inflation has on the growth in nominal GDP over decades.

Incidentally on a compounded annualized basis 109% in thirty years works out to +2.49% real GDP growth per year on average.

In short, when reading about or calculating how much the U.S. economy has grown or contracted over time you always want to use real GDP.

For those interested in seeing the official nominal and official real GDP numbers here are links from 1994 to 2024 from the St. Louis Fed for both. You can also change the dates to see GDP growth over different time periods.

Nominal GDP

We’ll cover some more criticisms, fair and unfair, of GDP measurement in the next column.

=====

Correspondent's note: Link to BEA tables breaking down (C)onsumption spending, Business (I)nvestment spending, (G)overnment spending, and Net Exports (Nx) by year.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.