Click here to read the original Cautious Optimism Facebook post with comments

12 MIN READ - From the Cautious Optimism Correspondent For Economic Affairs and other Egghead Stuff

Throughout late 2017 and early 2018 OPEC has enacted enormous

production cuts in a Saudi-led bid to raise oil prices from the 2016-nadir of

$26 per barrel. The production cuts are a reversal of OPEC’s multi-year price

war where the cartel pumped at near-full capacity despite plunging oil prices.

But the reversal towards production cuts marks an

abandonment of their previous strategy to put the newly conceived U.S. shale

oil industry out of business and return the global market to OPEC dominance.

Since U.S. shale is producing at record levels today even as OPEC tries to

raise prices, the strategy has clearly failed and OPEC has effectively cried

uncle. Why did OPEC think they could knock out their new competitor and why

didn’t the plot succeed?

LEADING UP TO THE PRICE WAR

Early this decade U.S. shale oil producers were for the

first time able to pump oil profitably at market prices that hovered between

$80 and $100 per barrel. Spurred on by new hydraulic fracturing technologies and

production techniques, oil and natural gas production boomed in areas like the

North Dakota Bakken and South Texas Eagle Ford formations. After decades of

steady declines, American oil production began to rise rapidly early in the

2011-2014 period.

OPEC, whose cartel of nationalized oil companies has enjoyed

control of a large share of world oil production capacity, saw U.S. shale oil

production as a new threat to not only their dominance, but the ability to

partially control world prices through coordinated production increases and

cuts among its members. True, some OPEC members “cheated” from time to time and

continued to secretly pump oil despite agreements not to, and the result was

OPEC was often not able to place world oil prices exactly where it wanted, but

the appearance of a new and very large non-OPEC producing nation would greatly

undermine OPEC’s long-standing leverage. Cartel leaders, particularly Saudi

Arabia, correctly identified U.S. shale as a threat and plotted to eliminate it

through a price war.

As shale oil poured out of the USA, the ballooning supplies

pushed oil prices below the long-standing $80 floor in late 2014. Once oil

prices fell below shale breakeven points, U.S. shale producers predictably cut

back on now unprofitable projects. But OPEC continued to pump at full capacity

since, after all, its conventional oil production costs were lower. However the

real objective this time was to drive prices so low that the entire U.S. shale

industry was bankrupted and wiped off the map.

A little-reported complication for OPEC is that despite

lower production costs on conventional Middle Eastern oil, OPEC member governments

are heavily reliant on revenues from their national oil companies to finance

their fiscal budgets and operations. Saudi Arabia for example is estimated to

have a breakeven production price of only $12, but it spends more than $50 of each

barrel’s revenue to fund government programs (the exact numbers are a secret

but experts believe these estimates are close). So as OPEC’s refusal to cut

production drove oil prices down further and further, many member countries

actually began to lose money as their government expenditures outstripped

per-barrel revenues.

Over the 2005-2014 decade as oil prices usually hovered well

over $80 Saudi Arabia and other OPEC members were able to produce profitably,

fund their government operations, and still enjoy profits that were diverted

into burgeoning reserve funds. But in 2015-2017, even as oil prices fell to

$50, then $40, and even $30 they planned to tap into those reserves and wait

out the price war until competition from U.S. shale was bankrupt—driven out of

business by losses. Then, according to the plan, OPEC would recapture its

traditionally dominant market share, cut production, raise prices back to

$80-$100 or higher, and enjoy enormous profits that replenished their diminished

reserve funds.

This is the classic strategy of so-called “predatory

pricing” which dominates mainstream economic thinking in the monopoly and

antitrust field. Drive prices down to the point of losses, outlast your

competition with your war chest of reserves that allows you to better withstand

those losses, and then when no competitors remain establish a monopoly that

allows you to jack up prices, replenish your war chest, and go on to enjoy bonanza profits that gouge the consumer forever.

Yet the strategy failed and after three years Saudi Arabia

and OPEC threw in the towel. Why?

THE PREDATORY PRICING FALLACY

The theory of predatory pricing has been with us since the

late 19th century when Ida Tarbell wrote her fallacious muckraking newspaper

series accusing John D Rockefeller’s Standard Oil of the practice. In the

century-plus since the idea has been propagated among academics and the media,

and it easily caught on with a (mostly uninformed) general public since it

appeals to a victimization mentality that proposes consumers are helpless in

the face of a market leading firm with enough power to drive all competition

out of business through lowering prices and then enjoy an abusive 100%

monopoly market share.

Such was the idea OPEC had of regaining their dominant

market share, encouraged undoubtedly by their own economic advisers who they’ve

sent to study at American Ivy League universities to study mainstream economics

for decades.

However in practice no one has ever been able to produce an

example of a firm that successfully achieved and then held a monopoly market

share with this strategy. A few firms that achieved close to 100% market share

such as Standard Oil and ALCOA did so not through predatory pricing, but rather

through relentless innovation and cost-cutting that continuously benefited consumers.

Companies like Standard Oil and Alcoa consistently grew their market shares

profitably, never by incurring years of losses to destroy competitors followed

by giant price hikes. OPEC’s failed attempt to drive out its competition is

another example that fails to prove the theory.

Furthermore any examples of coercive monopolies that have

abused consumers with impunity have all been monopolies established and

protected by government legislation—not free market practices. AT&T

famously gouged consumers on long-distance telephone rates from the end of

World War I to its breakup in the early 1980’s, but what’s less well known is

that AT&T was formed by an act of Congress that forced all of Bell

Telephone’s competitors to merge into a single entity (at the urging of Bell

incidentally, which was losing market share to new competitors) and then

granted the new national telephone company a monopoly on all long-distance

service. Most cable television operators are granted local monopoly licenses by

municipalities in exchange for broadcasting certain content “in the public

interest.”

In fact, not only is empirical evidence lacking that

predatory pricing has ever worked, the theory itself is full of holes.

University of Chicago’s John S. McGee famously wrote in his late 1950’s paper

on Standard Oil that predatory pricing was a flawed theory and irrational

strategy for several reasons. Loyola University economics professor Thomas DiLorenzo

sums them up as follows:

1. “As an investment strategy, predatory pricing is all cost

and risk and no potential reward. The would-be 'predator' stands to

lose the most from pricing below its average cost, since, presumably, it

already does the most business. If the company is the market leader with the

highest sales and is losing money on each sale, then that company will be the

biggest loser in the industry.”

2. “There is also great uncertainty about how long such a

tactic could take: ten years? twenty years? No business would intentionally

lose money on every sale for years on end with the pie-in-the-sky hope of

someday becoming a monopoly.”

3. Even if a firm was able to withstand years of losses and

finally establish a monopoly, “nothing would stop new competitors from all over

the world from entering the industry and driving the price back down, thereby

eliminating any benefits of the predatory pricing strategy.”

Thomas Sowell adds yet another contradiction in the theory,

one that is particularly relevant to the OPEC story:

4. “Even the demise of a competitor does not leave the

survivor home free. Bankruptcy does not by itself destroy the fallen

competitor's physical plant or the people whose skills made it a viable

business. Both may be available-perhaps at distress prices-to others who can

spring up to take the defunct firm's place.”

In the case of U.S. shale, OPEC wasn’t even a market firm

but rather a cartel of coercive government-sponsored national oil company

monopolies. And yet even with all its governmental powers OPEC could only

succeed in bankrupting some operators, but hardly all.

And even some of the bankrupt producers reorganized and

resumed operations with a cleaner balance sheet. Those that ceased operations

altogether simply capped their wells and sold the assets off at firesale prices

to other firms. The buyers, who obtained the already drilled wells at very low

cost, could now operate without the burden of heavy debts that plagued the

original producer.

So now if OPEC were to cut production and raise oil prices

back to $80-$100, they would face the same competing wells again but run by

producers who enjoy lower costs due to lightened debt loads and smaller

interest payments.

So according to theory skeptics, in the end the market share

picture would not change all that much only that Saudi Arabia and other OPEC

members would have burned through decades of reserve funds that were lost in

the trade war.

ENDGAME

As the price war dragged on through 2015, 2016, and most of

2017, the Kabuki theater performance played out exactly as predatory pricing

skeptics would have predicted—with two additional twists, both of which worked

against the Saudis (more on that in a moment). OPEC continued pumping and oil bottomed out at a shocking

low of $26.

Several smaller, higher cost shale players did go bankrupt. Some

reorganized and stayed in business. Others sold off assets in bankruptcy

auctions (assets that continued to operate under new production companies) and

some ceased operations and capped wells—assets that lie dormant and wait for

oil prices to rise again before producing.

But most shale players and virtually all of the major U.S.

oil and natural gas players weathered the storm and survived, even as profits

fell sharply or they incurred losses.

Meanwhile OPEC member states burned through their reserves

at an alarming rate. By some estimates Saudi Arabia’s reserves were down over

40% in just 2-1/2 years and were still falling rapidly in early 2017.

Reserve funds that had taken decades to build up were being

decimated in just a few short years. In a recent 60 Minutes interview with

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, one of Saudi Arabia’s top economic advisers

confessed to CBS that the kingdom was heading toward a major sovereign

financial crisis in a few years if it did not change course.

Hence in late 2017, seeing most U.S. shale and conventional

energy E&P players still in business and watching their own reserves

dwindle, the Saudis threw in the towel and called for the first of what would

become a series of production cuts to raise prices.

Now in early 2018 oil

prices are off their $26 lows hovering near $70, but U.S. shale is still here

and producing more than ever. If OPEC’s goals were to incur losses in exchange

for eliminating the U.S. shale oil industry, they succeeded only in the first

and failed miserably in the second.

In the end the OPEC predatory pricing scheme has been a

giant flop that has cost them hundreds of billions of dollars.

To add insult to injury, two unexpected twists added to

OPEC’s failures.

First, during the 2014-2017 price war, shale oil technologies

continued to make revolutionary progress and production costs plummeted even

further. Even if breakeven prices for shale had remained $60 or $70, OPEC’s

plot would have flopped anyway, but lower production costs only accelerated its

demise. New and improved 3-D geological surveying, horizontal drilling, drill

bit, fracturing fluid and computerized drilling technologies reduced well

completion times, increased oil and natural gas well recovery rates, and cut

production costs nearly in half again.

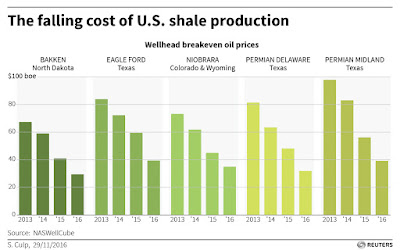

The decline varied from shale formation

to formation, but as you can see here typical breakeven costs have fallen by

around half in most areas. For example falling from about $68 to $30 in the

North Dakota Bakken, $82 to $40 in the Eagle Ford, and $81 to $32 in the

Permian Delaware formation.

And this data is already old—from 2016. Production costs in

early 2018 have surely fallen further. U.S. shale turned out to be a lot more

resilient than OPEC had hoped.

The other twist is that oil and natural gas production has

opened or expanded in several new formations across the country since the price

war began. In 2014 production came predominantly from the North Dakota Bakken

and South Texas Eagle Ford. But in the years since oil and natural gas have

poured out from the Utica and Marcellus formations in the north Appalachians,

the Niobrara of Colorado and Wyoming, and the North Texas Barnett to name just

a few.

But most of all, a herculean production boom has restarted in the West

Texas Permian.

The Permian was a major conventional oilfield in early 20th

century—part of the historical Texas boom seen in old Hollywood films. However

starting in the 1970’s production of conventional oil dwindled as easy-to-reach

oil was exhausted and the Permian was mostly abandoned—thought no longer

profitably recoverable.

However underneath the conventional fields were vast

additional supplies of oil and natural gas trapped in shale formations, and the

shale fracturing revolution has reopened the Permian for business. Recovery of

its tens of billions of barrels of shale oil and nearly 100 trillion cubic feet

of shale natural gas has ramped up quickly, and in early 2018 the Permian alone

already accounted for approximately one-quarter of all U.S. oil production;

approximately 2.5 million barrels a day.

As OPEC continues to cut production and oil prices creep up

slowly, the cartel’s leaders have been forced to watch helplessly as U.S. shale

producers move in to fill most of the gap. In the past OPEC’s cuts may have

produced prices topping well over $100 by now. Instead they are in the high

$60’s. Their only hope now is that worldwide oil demand will grow rapidly

enough that even U.S. shale will not be enough to prevent triple-digit oil

prices. But even if that day eventually comes, the USA will also share in the

spoils with its own domestic windfall profits and high-paying American jobs.

The U.S. is already forecast to be the world’s largest oil producer in 2018 and

a net energy exporter by 2023. Its burgeoning energy exports will also make a

sizable dent in the highly-publicized trade deficit, and a lot less money will

go to parts of the world that many argue “hate us.”

And of course OPEC’s dream of destroying U.S. shale and

capturing its old dominant market share is a distant memory. The grand plot

failed and the cartel’s members burned through a fortune of losses—losses that

were effectively wealth transfers to the world’s energy consumers in the form

of a windfall plus, unfortunately, national and state governments that viewed

lower prices as an opportunity to stealthily impose energy tax increases. OPEC

has learned the hard way that mainstream antitrust and monopoly economic theory

usually doesn’t work.

Perhaps they shouldn’t have sent those advisers to Ivy

League schools and considered alternative free-market-friendly universities

instead. Studying at University of Chicago, George Mason, or San Jose State

instead of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton would have saved them tens of thousands of dollars in tuition costs—and a few hundred billion in oil losses.